BEMIDJI, Minn. — EDITOR'S NOTE: The full story will air tonight on KARE 11 at 10 p.m.

Nurse Practitioner Stephanie Lundblad had just started working at the Beltrami County jail in August 2018 when she was instructed to look in on an inmate. Staff warned her he was faking being paralyzed and incontinent.

But the moment she saw him, Lundblad said she knew otherwise.

She said the smell of sweat and urine overwhelmed her as she walked into Hardel Sherrell’s cell.

Lundblad said he had tears streaming down his face and was pleading for his life.

“He couldn’t even stand up. He could barely talk. He could still cry,” she said, speaking publicly about his death for the first time.

“It looked like a man who was suffering, that was sick. That was dying,” Lundblad said.

When she checked his vital signs, she found his heart rate and blood pressure were both high, his oxygen saturation was too low, and the right side of his mouth was drooping.

Fearing he had a stroke, she ordered that Sherrell be checked at a hospital. But a few days later, he died after other jail staff continued to believe he was faking.

Devastated, Lundblad sent letters to the state Department of Corrections (DOC), Minnesota Board of Medical Practice and the state Board of Nursing, detailing Sherrell’s neglect before he died.

Those letters would ultimately help trigger an FBI investigation into Sherrell’s death and fuel statewide reforms being considered by the legislature this week.

“I want justice for Hardel. I want what happened to Hardel to never ever happen to anyone again,” Lundblad said. “I want accountability.”

Letter ignored first time around

The conditions that led to Sherrell’s death might never have become public if not for Lundblad’s complaints.

The original review of the death by the Minnesota DOC, which oversees the state’s jails, found “no violations.”

DOC Commissioner Paul Schnell later acknowledged that the department had received Lundblad’s complaint letter, but apparently the jail inspection unit in a prior administration let it slip through the cracks.

Nearly two years passed.

It wasn’t until Sherrell’s mother, Del Shea Perry, repeatedly and publicly raised questions about the investigation, that Schnell said the DOC again reviewed Lundblad’s letter.

She had detailed finding Sherrell wearing a diaper soaked with urine that jail staff refused to change. When she ordered that he be sent to an emergency room, she said officers initially refused to help lift him into a wheelchair.

She wrote that even though Sherrell’s vital signs and an electrocardiogram were abnormal, correctional officers “were speaking very negatively about Hardel, saying he was faking his situation.”

“He told me no one was believing him,” Lundblad wrote.

DOC Commissioner Paul Schnell said the letter finally prompted a more thorough review.

This time, the DOC looked at more than 1,000 records and jail videos and concluded there were “regular and gross violation of Minnesota Jail standards.”

Hardel’s mother has filed a federal lawsuit against the Beltrami County jail, MEND Correctional Care and Sanford Hospital.

In court filings, all three entities have denied wrongdoing.

The lawsuit, Perry’s protests and Lundblad’s complaints also sparked an ongoing investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Lundblad said she has been interviewed by the FBI.

Preventable deaths

The Ramsey Medical Examiner found that Sherrell died of pneumonia and brain swelling, but as part of Perry’s lawsuit, a private autopsy revealed he was suffering from a rare, but treatable, condition called Guillain-Barre syndrome. The disorder causes the body's immune system to attack the nerves causing paralysis.

Sherrell’s case and other preventable inmate deaths revealed by KARE 11’s “Cruel & Unusual” investigation prompted legislation that would require counties to provide better care to inmates.

It would also grant DOC more authority to investigate deaths and take swifter action to force corrections.

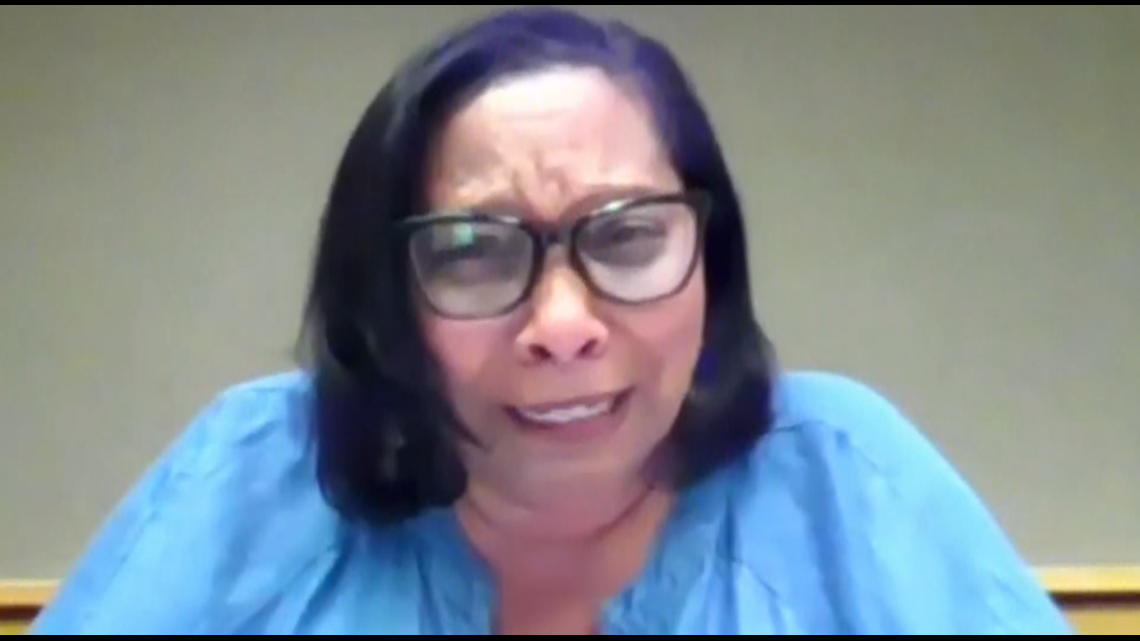

On Saturday – the day before Mother’s Day – Perry testified in support of the bill during a House and Senate committee. In tears, she recounted the final days before the death of her only son.

“Hardel Sherrell walked into the Beltrami jail, and let me put emphasis on ‘he walked,’” she said. “Nine days later he left in a body bag.”

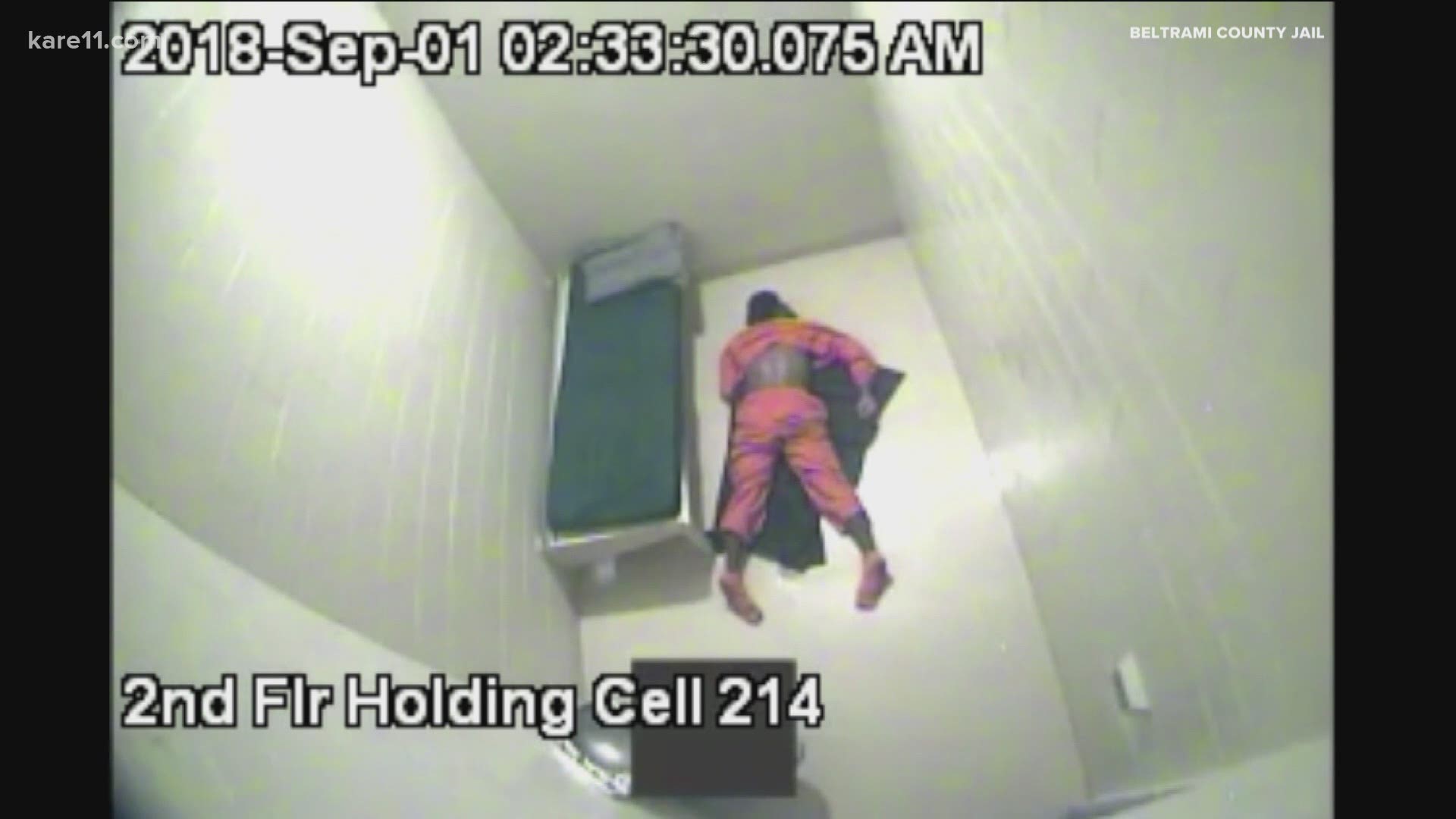

Surveillance video captured his slow deterioration into paralysis and agonizing pain as he often lay on a floor for hours. The only person who appeared to believe Sherrell was Lundblad.

Perry credited Lundblad for overriding jail staff and demanding that Sherrell be taken to a hospital.

At the ER, however, records indicate an MRI did not reveal irregularities. After a jail guard told the hospital doctor that Sherrell was faking, he was diagnosed with “malingering” with unspecified weakness and fatigue.

Sherrell returned to the jail with instructions to “SEEK MEDICAL ATTENTION IMMEDIATELY” if he experienced “worsening weakness, difficulty standing, loss of control of the bladder or bowels or difficulty swallowing.”

Despite having all those symptoms, he was never returned to the hospital.

Sherrell died two days later – on his jail cell floor.

“Hardel should be here today,” Perry said. “Hardel died a senseless death. Egregious. They let that baby lay on that floor, a cold jail floor.”

She credited Lundblad’s reports for first revealing the truth about her son’s death.

‘Witnessed a murder’

Before she walked into Sherrell’s cell, Lundblad had been a federal prison nurse for two years.

She was hired by MEND Correctional Care, which provides services for nearly a third of the state’s jails and is now embroiled in several lawsuits over inmate deaths.

Lundblad’s first assignment with MEND was to provide care for inmates at the Beltrami County jail. When she found Sherrell, she told KARE 11 it was clear that he was suffering.

“We treat animals in kennels better than he was being treated,” she said. “I knew that if he didn’t receive medical care immediately that he probably wouldn’t make it.”

After sending Sherrell to the hospital, she finished her shift, not knowing that he was discharged and sent back to the jail. Two days later in a meeting with the owner of MEND, Dr. Todd Leonard, she says she learned of his death.

She would later write in her report to the DOC and Medical Board that Leonard acknowledged being warned “Hardel was deteriorating” but never saw him because he thought Sherrell was “faking his illness.”

She wrote that he told her “not to jump to conclusions” because that “could jeopardize his company.”

She said that she resigned immediately.

“I felt like I had witnessed a murder,” she told KARE 11.

As the legislature continues to debate the jail reforms, Lundblad said she’s still haunted by what happened to Sherrell.

“When you see another human being suffering that way, it changes you,” she said. “And that memory doesn’t go away.”