Dr. Todd Leonard sat before the Minnesota Board of Medical Practice, ready for his punishment.

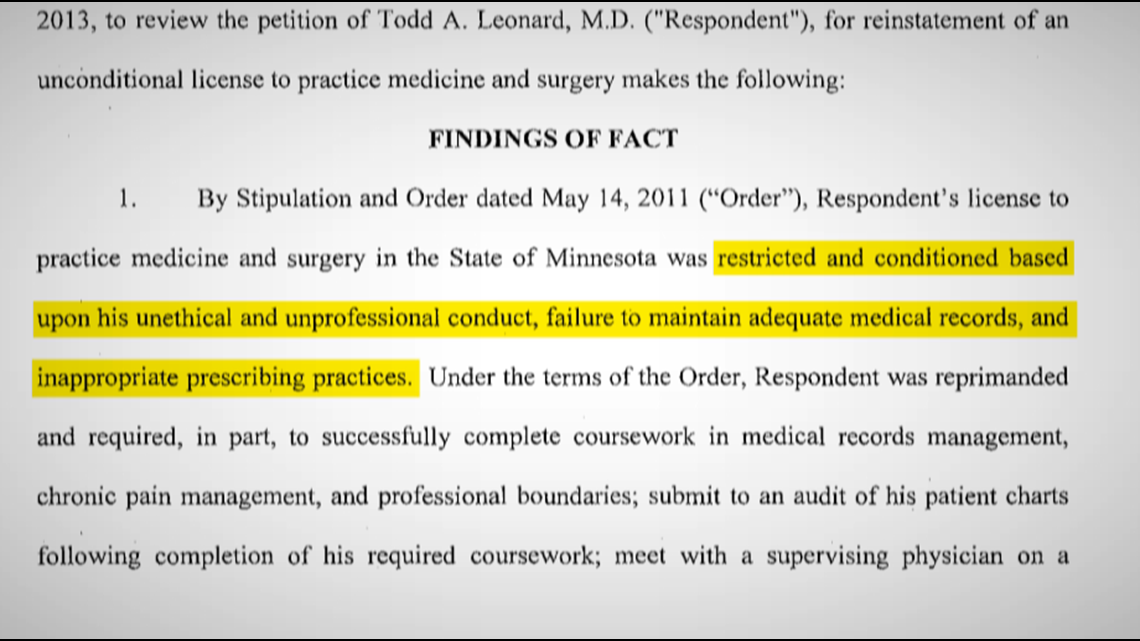

An investigation by the state Attorney General’s office revealed a long list of what the board would call “unethical and unprofessional conduct.”

Among them: records show he repeatedly prescribed narcotics without documenting if his patients actually needed them; if he put them on the drugs, he often failed document their risk for suicide or addiction, then failed to see if they actually worked or if his patients were stealing the drugs.

As a result, in 2011 the Board reprimanded him, fined him, and restricted his license.

That was nearly 10 years ago.

Now, Leonard is arguably the most important physician for thousands of Minnesota’s jail inmates.

MEnD Correctional Care, the company Dr. Leonard founded around the time of the board’s sanction, has grown so vastly in the last decade that it now provides health care to about a third of the state’s jails. On any given day, MEnD cares for an inmate population of 2,700, by far the largest provider of any in the state, according to KARE 11's analysis of court and contract records.

A KARE 11 investigation reveals Dr. Leonard’s company now faces allegations in civil lawsuits of record falsification and inadequate care that led to preventable deaths.

Dr. Leonard declined KARE 11’s request for an interview, so our report is based on a review of thousands of pages of court and medical records, as well as interviews with attorneys, former inmates, and families of inmates who died while under MEnD’s care.

Cutting corners?

In addition to contracts with Minnesota jails, the Sartell-based MEnD has also signed contracts to take over the medical care for several jails in Iowa and Wisconsin and one in Illinois.

Dr. Leonard has grown his business through a pitch that counties like to hear: MEnD can save taxpayers money while still providing cheaper, but high quality health care.

Critics claim MEnD’s care has come at a high cost.

As Leonard’s business has grown, it has taken in at least $51 million in taxpayer dollars over the last decade, records show.

During that time, the list of inmates who have died while MEnD was the health care provider has also grown – at least 25 since 2015, KARE 11 has found.

Several of those deaths have resulted in federal lawsuits accusing Dr. Leonard and MEnD of failing to provide necessary treatment while cutting costs and corners by hiring inexperienced, unqualified staff to work with inmates with significant medical needs.

Among those cases:

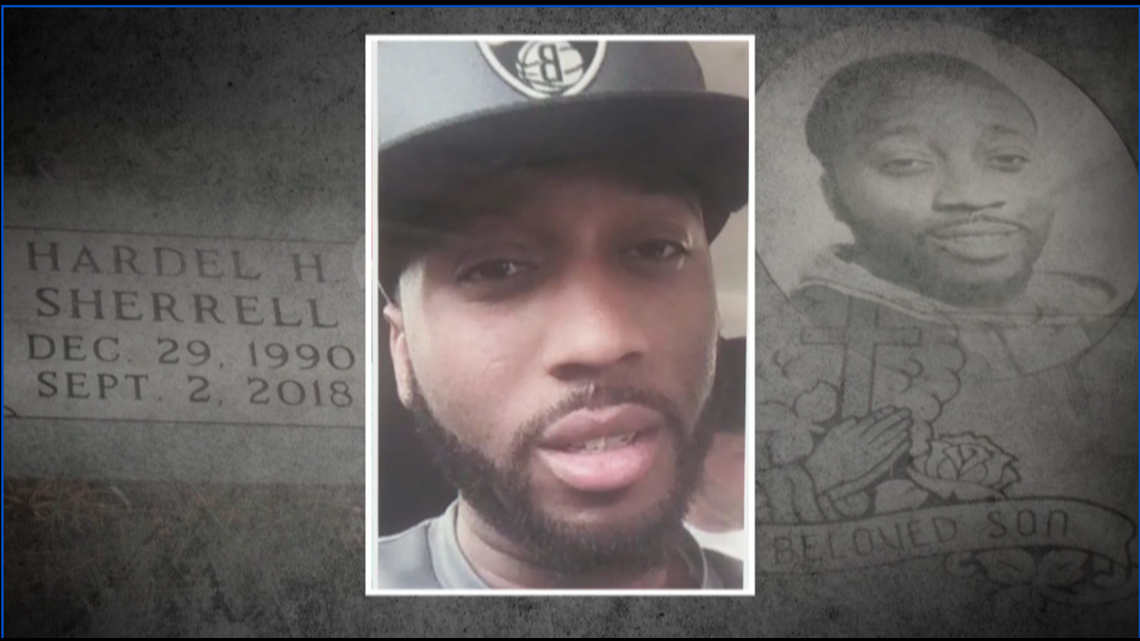

Hardel Sherrell, who died a slow, agonizing death over several days at the Beltrami County jail after his jailers and MEnD providers believed he was faking paralysis.

Bruce Lundmark, another Beltrami inmate who repeatedly asked to see a doctor but was denied before being shipped off to another jail, where he died from an internal hemorrhage shortly after arriving.

Abby Rudolph, who died after vomiting for days in the Clay County jail while suffering from drug withdrawal without being provided medication.

James Lynas, who killed himself in the Sherburne County jail after MEnD allegedly failed to provide him with mental healthcare despite records showing he was severely depressed and had considered suicide.

Dr. Leonard and MEnD have repeatedly declined requests for comment from KARE 11 on his health care record and business practices, citing a desire to protect patients’ health records as well as ongoing litigation.

The company issued a statement in July saying, “By way of context, over the last decade, we have provided quality medical care to thousands of individuals in correctional facilities across the upper Midwest. Over this time, we feel that we have made a tremendously positive impact on our individual patients, and our industry as a whole. The work we do is challenging, but it needs to be done with compassion, care and professionalism. We work hard to live up to those standards and are proud of the quality healthcare that we have delivered.”

Who’s watching jails?

Who actually checks on whether MEnD has provided quality health care is unclear.

Though the company is paid with county tax dollars, MEnD operates with no real state oversight. The state Department of Corrections (DOC) licenses jails and does inspections following an inmate death, but it has no authority over the medical care provided.

“It is entirely a contractual relationship between the counties and the provider,” said DOC Commissioner Paul Schnell.

That leaves state medical boards to use the state Attorney General to investigate individual physicians and nurses, but only when they get complaints. Those cases can take years to be investigated and are handled in secret.

KARE 11 has confirmed with multiple sources that Leonard is under Board investigation once again after a former MEnD nurse sent a complaint about him following Sherrell’s death.

Leonard’s history

Leonard started his career as a family practice physician after graduating from the University of Minnesota Medical School in 1996.

About 10 years later, in 2007, the Minnesota Medical Board began receiving complaints about Leonard’s practice, saying that he had prescribed excessive amounts of pain medication from 2001 and 2006 to a patient and “exhibited unprofessional boundaries,” according to public records.

In November 2006, Leonard became the Medical Director for the Sherburne County jail. He would later say in a newspaper interview that he initially had no interest in corrections – and had never before set foot in a jail – until he got a call from a childhood friend who also happened to be the Sherburne County Sheriff.

In the story, Leonard said the sheriff asked him to review the jail’s medical care. After Leonard made recommendations, the sheriff told Leonard that his proposal “is probably going to save taxpayers of this county a half million dollars a year,” and asked him to become the provider. He agreed.

The next year, Leonard also became the Medical Director of the Mille Lacs County jail and then in 2008 officially formed his business: MEnD Correctional Care.

By then, the state Attorney General’s office was already investigating Dr. Leonard’s practices following the complaints made to the medical board.

Leonard met with the board in the fall of 2008 to discuss “allegations regarding documentation, prescribing practices and procedures and professional boundaries.”

A committee decided to continue the case to allow the Attorney General’s investigators to do an audit of his practice.

Medical Board findings

According to the board, a review found “multiple” failures with his documentation. His notes were “frequently cursory, incomplete and illegible.” He often failed to document a diagnosis, adequate patient history, or a rationale for prescribed medications.

When it came to prescribing narcotics, the investigation found he failed to document why those patients needed them or show that he assessed patients’ risk of addiction. He failed to implement control over those narcotics, or drug-test his patients, while also failing to identify patients’ who were trying to get drugs.

Leonard would meet with the board again in February 2010, where he “acknowledged his failure to consistently document his patient charts in a complete and legible manner.”

Finally, in a stipulated agreement in May 2011 the Board reprimanded Leonard, ordered him to pay an $11,743 civil penalty and restricted his license for two years. In addition to requiring he take more training in record keeping and chronic pain management, his practice had to be supervised by a board member and another physician.

While under that supervision, Leonard would take over the medical care for six more jails. One of the doctors who supervised him, Roger Boettcher, who practices in the Mille Lacs area, said in an interview with KARE 11 that he agreed to the supervision because he was a family friend of Leonard’s.

Boettcher said in the interview that he had no concerns as he reviewed Leonard’s work and saw no problems with him growing his business.

The board member who supervised him, psychologist Gerald Kaplan, said while working with Leonard, “I never had any complaints about the services he provided.”

“He was fully compliant with his order,” Kaplan added. “And not everybody is.”

Sanctions end, business grows

After the medical board voted to end Leonard’s sanctions in September 2013, his business would boom, picking up 31 more jails over the next eight years.

Lawsuits would follow. The first was filed in 2014, involving Stearns County inmate Kyle Allan Baxter-Jensen, who tried twice to kill himself at the jail.

In his first attempt, he was able to obtain razor despite his history of mental illness. He used it to slice open his throat, according to a federal lawsuit filed by his family.

After surgery to close his wounds, a hospital doctor ordered that he “will require psychiatric evaluation,” records show.

Baxter-Jensen recovered and went back to the jail. But the lawsuit claims the psychiatric evaluation never happened. Instead, it says Dr. Leonard discontinued his suicide risk classification after the inmate told his jailers he was no longer suicidal.

Less than a month after his first suicide attempt, Baxter-Jensen obtained another inmate’s razor and cut his throat again. He bled to death in jail.

Baxter-Jensen’s family received $1.45 million in 2016 as part of a settlement in the case. MEnD paid more than half of that -- $850,000 – according to Bob Bennett, an attorney representing the family in the case.

Stearns County would end its contract with MEnD the next year, with Leonard saying in a deposition it was due to “political collateral damage in town.”

But the lawsuits alleging inadequate care would continue.

Lawsuit allegations

MEnD hires nurses, physician assistants and medical technicians to staff individual jails. But since founding his company up until at least the end of last year, Leonard remained MEnD’s only licensed physician in Minnesota, records show.

Under state law, that gives him the final responsibility for any medical decision for an inmate under MEnD’s care. That includes ordering a prescription, sending someone to a hospital, ordering an x-ray or adequately diagnosing a mentally ill patient.

With contracts to provide medical care in more than 30 jails, on any given day Dr. Leonard has been the only doctor responsible for as many as 2,700 inmates.

KARE 11 identified nearly a dozen lawsuits already filed – and others being prepared – against MEnD, accusing Leonard of being stretched too thin for the thousands of inmates under his care. They claim MEnD deliberately refused to send inmates to more qualified specialists.

Questionable evaluations?

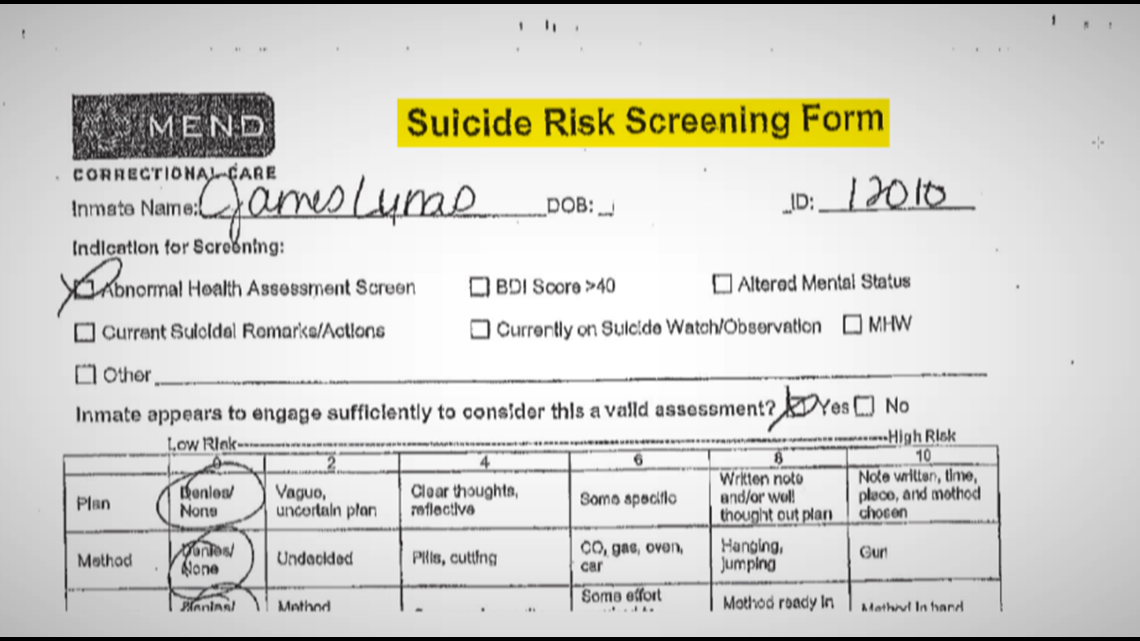

Some of those cases involve suicides in which MEnD is accused of using questionable evaluations that often leave a nurse or nurse practitioner to provide mental health care to someone who is mentally ill, rather than a qualified therapist.

In depositions, Leonard has defended that practice, saying “by virtue of their education and credentialing, (they) qualified as qualified mental health professionals.”

But even some of MEnD’s own nurses have refuted that claim. In one case, three of the nurses who cared for a mentally ill inmate said in depositions they were not qualified mental health professionals.

That inmate, James Lynas, was booked into the Sherburne County jail in 2016 for a DWI. Records show a MEnD nurse used company-approved forms to evaluate him for drug withdrawal and suicide risk. Had he scored high enough, it would have automatically required intervention to see a higher level medical provider.

Even though his medical records show Lynas was withdrawing from drugs and expressing suicidal thoughts, according to the MEnD evaluation he scored too low for his case to be reviewed by a mental health professional.

Nine days later he died by suicide.

KARE 11’s analysis of state records recently exposed that the rate of jail deaths in Minnesota resulting from suicide is double the national average.

A lawsuit revealed that the forms used to screen Lynas were created and copyrighted by Dr. Leonard. But under oath in a deposition, he said he didn’t remember where he got the information to create the forms – or how he set a threshold to see a higher-level medical provider.

A federal judge in the lawsuit wrote the evaluations could be considered “arbitrary.”

Before he died, Lynas was given another assessment using a nationally recognized test. By that standard he was scored “severely depressed.” However, records show he was never seen by a mental health specialist. The highest level of treatment he received before he killed himself was an antihistamine prescription that is sometimes used for depression.

Falsified records?

MEnD’s suicide screening form is now key evidence in another federal lawsuit against the company. It accuses a MEnD nurse of trying to cover up details of medical care before another inmate’s death.

In 2017, Stephanie Bunker died by suicide while in the Beltrami County jail. Records citied in the lawsuit show both her jailers and MEnD staff knew she had attempted suicide earlier – and that a nurse scored her on a MEnD form at a threshold that would have required higher intervention.

After she hung herself, the nurse filled out another form that changed her score to be below the threshold, according to the suit.

In court filings, MEnD has denied a cover-up and overall responsibility for her death.

“Are you saying records were changed after she died?” KARE 11’s A. J. Lagoe asked Robert Bennett, the attorney who filed lawsuits against MEnD in both the Lynas and Bunker cases.

“Yes,” Bennett replied. “From ‘You need to go see a doctor’ to ‘You don’t need to go see a doctor.’”

His assessment of the company after reviewing records in those and other cases: “They’re not equipped to provide constitutionally required medical or mental health care.”

Delayed care?

Even when a MEnD employee recommended additional care, a whistleblower claims Dr. Leonard delayed it – in a case that allegedly cost an inmate his life.

In a formal complaint to the state medical board, a nurse who once worked for MEnD said she was sitting across from Dr. Leonard when he took a phone call about the death of Hardel Sherrell in the Beltrami County jail.

Days earlier, records show the same nurse had found Sherell on a mat soaked in sweat and urine, unable to walk or control his bladder. Although jailers thought he was faking his symptoms, she had him sent to the hospital.

Unable to identify an underlying problem, an emergency room doctor sent Sherell back to the jail with instructions to “seek medical attention immediately” if his condition worsened.

The whistleblower nurse says Dr. Leonard told her that he had gotten calls through the Labor Day weekend telling him that Sherrell was deteriorating. Instead of having Sherrell re-examined immediately, the nurse said Leonard told her he had instructed the jail staff that Sherrell “could wait until after the holiday.”

Hardel Sherell died on his jail cell floor before receiving additional care.

The nurse says she when she told Dr. Leonard that she believed something had been very wrong with Sherrell, he defended his decision.

“Dr. Leonard then told me to not jump to conclusions,” she wrote. “He then said that jumping to conclusions could jeopardize his company.”

Although the nurse filed a complaint with Board of Medical Practice in 2018, no public disciplinary action has been taken. That led to a protest outside Board headquarters by members of Sherrell’s family and others demanding better medical care for inmates.

Sources have confirmed to KARE 11 that there is an active investigation into Dr. Leonard’s handling of Sherrell’s medical treatment.

Disclosure questions

Records show Leonard has not always been completely open about his legal and disciplinary history.

When Olmsted County was looking for a new health care provider in 2015, the county asked all applicants if they had any lawsuits pending. Despite the Baxter-Jensen case being filed the year before, Leonard left that question unanswered.

What’s more, the county also asked if any “current staff ever had their license suspended, revoked or put on conditional status?” Records show Leonard responded: “I am pleased to share that our staff have never had any of those disciplinary situations develop while performing their duties and services for our company.”

Asked by KARE 11 why he didn’t disclose his own disciplinary history, Leonard responded in an email:

“Our answer to Olmsted County was based on an assumption that the question applied only to staff working on a daily and direct basis with Olmsted County and is thus accurate.”

“I can’t imagine our County Attorney would have signed off on and advised us to go ahead and enter into the contract if they had been made aware of any of the challenges that you’re talking about,” said Olmsted Sheriff Kevin Torgerson.

However, he praised MEnD’s performance so far. “All of our staff down there are very excited and pleased with what MEnD has been doing for us,” he said.

For-profit care problems

MEnD is not the only for-profit provider to be the subject of scrutiny following inmate deaths. One of the largest, WellPath, for example, is a defendant in numerous lawsuits across the country.

Inmate advocates generally argue that public health departments are better suited to provide prisoner care. A Reuters analysis found that jails with private health contractors had higher death rates than those run by government agencies.

But providing public care is more expensive, said Alison Hardy, a senior attorney for the Prison Law Office.

Public health “is focused on keeping you healthy,” said Hardy, whose office has brought numerous lawsuits against for-profit inmate care providers across the country. “For-profit providers are going to provide the best profits they can with the context of doing the minimum required. It is not set up with the patient in mind.”

Citing a clear need for reform here in Minnesota, State Senator Chuck Wiger (DFL-Maplewood) says he’s working with the Department of Corrections to introduce legislation next month to strengthen how Minnesota investigates jail deaths and oversees medical care behind bars.

For the families of prisoners who have died in Minnesota jails, reforms can’t come soon enough.

“When is enough enough?” asked Hardel Sherrell’s mother, Del Shea Perry. “How many more people have to die?”

If you have something you think we should investigate, email us at: investigations@kare11.com