Stephanie Lundblad is still waiting.

It’s been nearly five years since she witnessed what to her felt like a murder: Hardel Sherrell’s agonizing death in the Beltrami County Jail, where guards and medical staff refused his pleas for medical help.

Lundblad, a nurse practitioner, was one of the few who tried to help Sherrell when she worked in the jail for Beltrami’s medical provider - MEnD Correctional Care. She resigned shortly after Sherrell’s death, then blew the whistle.

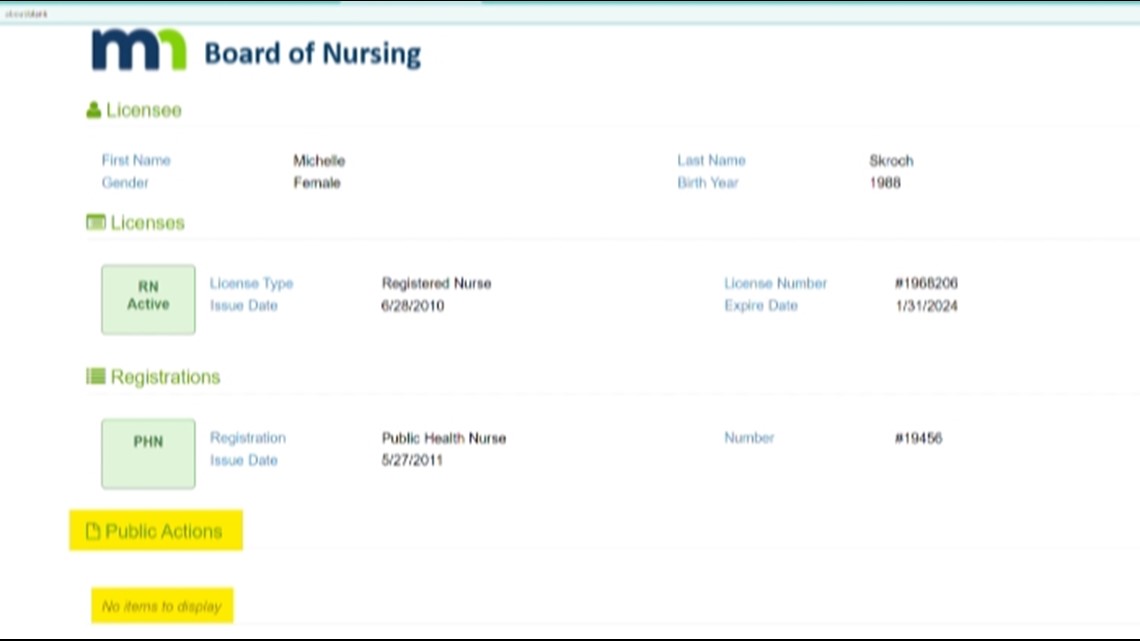

She filed complaints in 2018 with the state medical board against Doctor Todd Leonard, and with the Minnesota Board of Nursing against MEnD’s nursing Director, Michelle Skroch, who was directly in charge of Sherrell’s care in the last two days of his life.

Leonard, who never saw Sherrell but monitored his condition via telephone, had his medical license indefinitely suspended in early 2022.

An administrative law judge in Leonard’s case also called for the Board of Nursing to investigate Skroch’s “dereliction of duty and shocking indifference.”

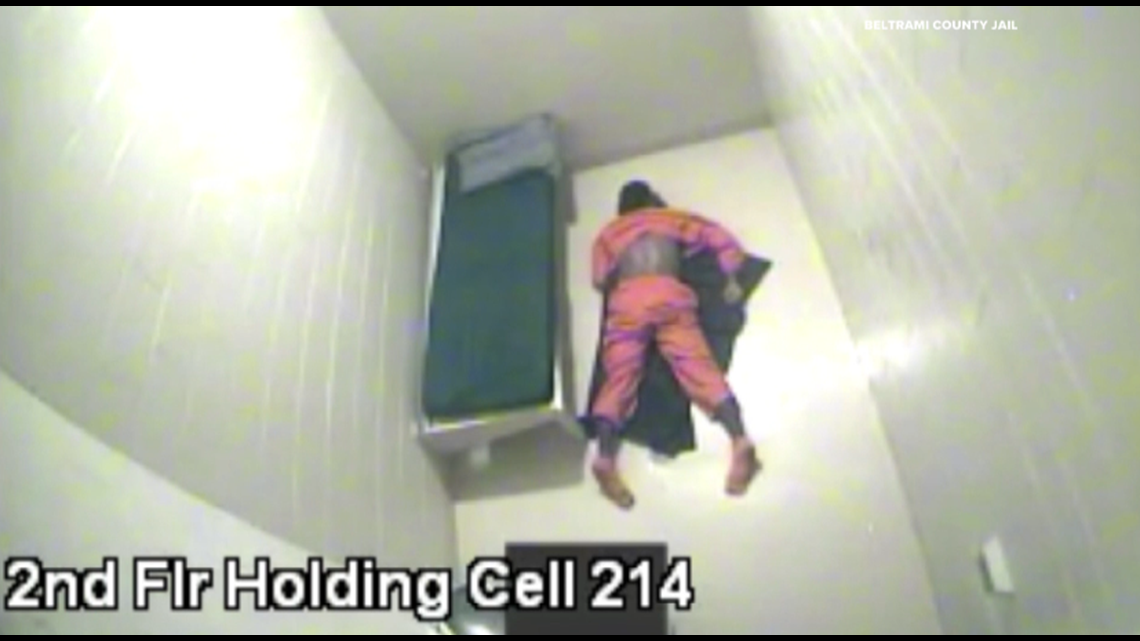

The nurse failed to provide care to Sherrell – or even check his vital signs – as he lay nearly lifeless on the floor of his cell wearing adult diapers soaked in his own urine, the judge found.

When KARE 11 first interviewed her in 2021, Lundblad was surprised the nursing board hadn’t taken action against Skroch. “It’s hard for me to understand when you can look at the documentation and the video footage and see what happened – and for there to be no action,” she said.

Two years later, and a year after the judge called for further investigation, there’s still been no action.

The nursing board website shows Skroch has an active license with no disciplinary actions listed.

Pattern of Delay

Skroch’s case is not unusual.

A KARE 11 investigation in 2020 detailed how – despite multiple complaints – the board failed to stop a nurse from repeatedly stealing medicine from patients, leaving an elderly woman in excruciating pain.

At the time, records showed the board rarely used its power to temporarily suspend nurses who face allegations of serious and dangerous misconduct. There was only one suspension per year in 2018 and 2019.

Now, a new investigation by the non-profit newsroom ProPublica documents how suspensions are still rare and nursing board investigations continue to drag on for months or even years.

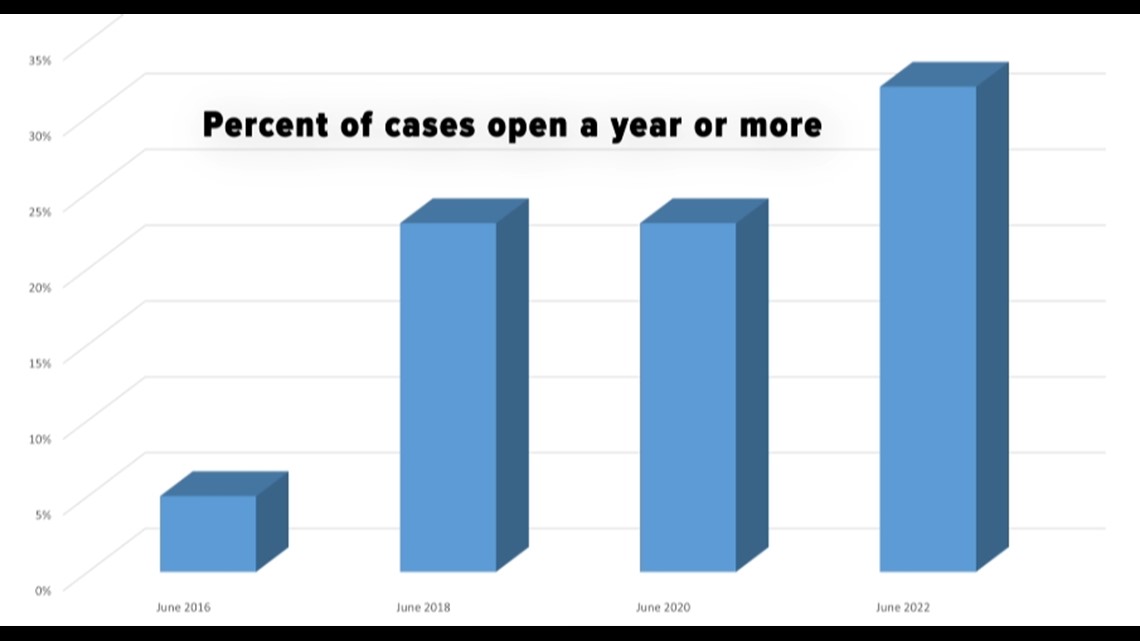

Despite a state law that requires complaints to be resolved within a year, the percentage of cases that go beyond that mark has soared from fewer than 5% in 2016 to 30% now, the data shows.

Woefully deficient care

When Lundblad treated Sherrell at the Beltrami jail in 2018, she sent him to an emergency room after finding him writhing in pain on a cell floor.

Doctors released Sherrell back to the jail with instructions to bring him back if his symptoms worsened. Instead, records show Skroch instructed jail staff not to assist him because she said there was nothing medically wrong with him.

After Sherrell’s death, Lundblad said she felt it was her duty to file a report with the state’s medical and nursing boards.

“As medical professionals we’re trained that if we see abuse or neglect that we report it,” she said.

In addition to failing to take his vital signs, video showed Skroch had only briefly peered into his cell twice and had missed that he was in distress: Sherrell was unconscious on the floor with a white substance coming out of his mouth.

The administrative law judge who ruled in Dr. Leonard’s case called the nurse’s care “woefully deficient,” “incompetent” and “negligent.”

Skroch declined to comment.

State law requires the board to notify complainants about the status of the investigation every 120 days. Yet Lundblad tells KARE 11 it’s been nearly two years since the board last notified her that the case was still being investigated.

Sherrell’s mother, Del Shea Perry, also wonders what has taken so long for the board to take action.

"I have no idea what the board is doing, and it sure as hell shouldn't take four years to investigate," Perry said.

Stealing meds, continuing to practice

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

A Star Tribune investigation in 2013 on the nursing board sparked a legislative audit, which found that the board acted too slowly when the public’s safety was at risk.

Prompted by the scrutiny, the legislature changed state law to give the board more power to suspend nurses, including temporarily removing them from practice while it investigates cases believed to pose an immediate risk to patients.

The board also began to dispose of complaints more quickly.

But that progress was short-lived, records show.

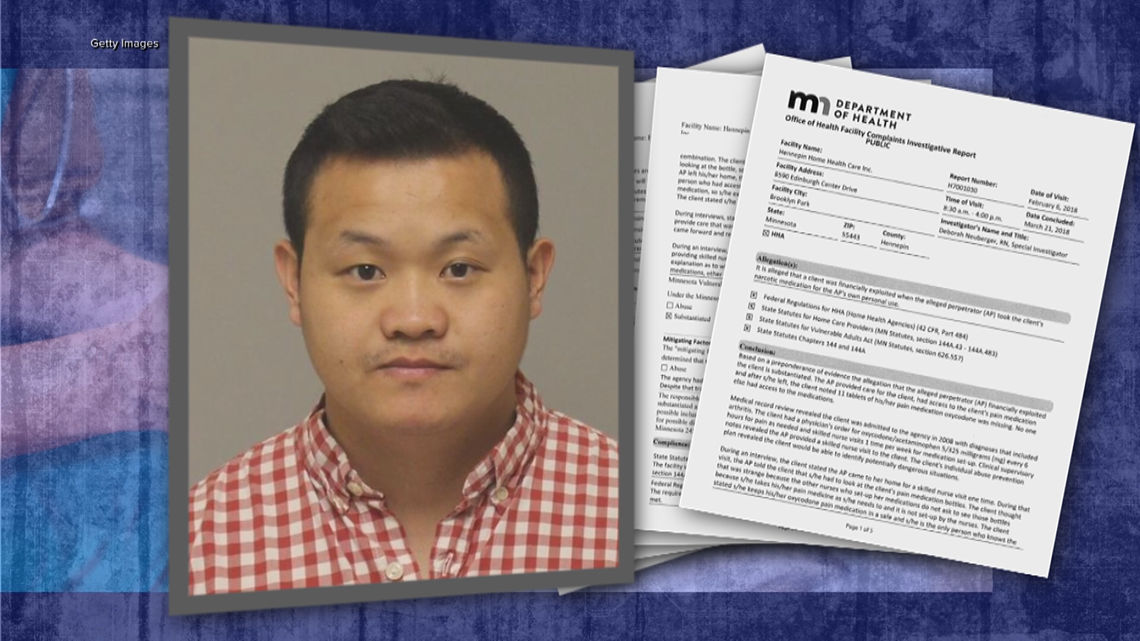

KARE 11’s investigation in 2020 highlighted multiple complaints involving nurse La Vang, accusing him of repeatedly stealing narcotics from patients in 2017 and 2018 — including one allegation validated by the state health department.

Because the board didn’t suspend his license, Vang was able to move from job to job at Minneapolis area home health agencies – allegedly stealing medication from multiple patients.

One of them was LaVonne Borsheim, who had powerful pain pills prescribed to her following a surgery.

Vang would later tell police that he stole Borsheim’s pills and replaced them with over-the-counter Tylenol, leaving her in agony.

Borsheim was in such pain that, “she asked God to take her home to heaven because she couldn’t go on,” her husband Roger Borsheim told KARE 11.

Acting on a tip from her family, police pulled Vang over and found pills and empty prescription bottles belonging to Borsheim in his car.

It wasn’t until after his arrest that the nursing board got Vang to sign an agreement to cease practicing. He later pleaded guilty in federal court to obtaining controlled substances by fraud and was sentenced to 18 months in prison.

The board staffer ultimately responsible for investigating and suspending Vang, Kimberly Miller, was tabbed as the Board of Nursing’s executive director in August 2021.

She did not respond to a request for an on-camera interview with KARE 11.

Not only are many cases taking longer to investigate, records show the state has been using its temporary suspension authority less often.

The board exercised that authority 55 times from 2014 to 2017, according to state data.

Since 2018, however, records show the board has issued only nine temporary suspensions.

In an interview with ProPublica, Miller said the agency is working to improve its performance.

“I think that we are on a good course at this point, and we’re making the changes that we need to, and learning to work as a team, and working out our system that I think is going to be really wonderful at some point,” Miller said.

ProPublica’s investigation uncovered vexing bureaucratic issues, and allegations of a toxic work environment at the nursing board leading to a wave of resignations. For the public, the result is investigations dragging on for months and years allowing potentially dangerous nurses to keep practicing.

Read ProPublica’s full investigation at this link.

ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. You can Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive ProPublica’s stories in your inbox every week.

Watch more KARE 11 Investigates:

Watch all of the latest stories from our award-winning investigative team in our special YouTube playlist: