SAINT PAUL, Minn. — A federal grand jury is investigating the 2018 death of a Beltrami County jail inmate, KARE 11 has learned.

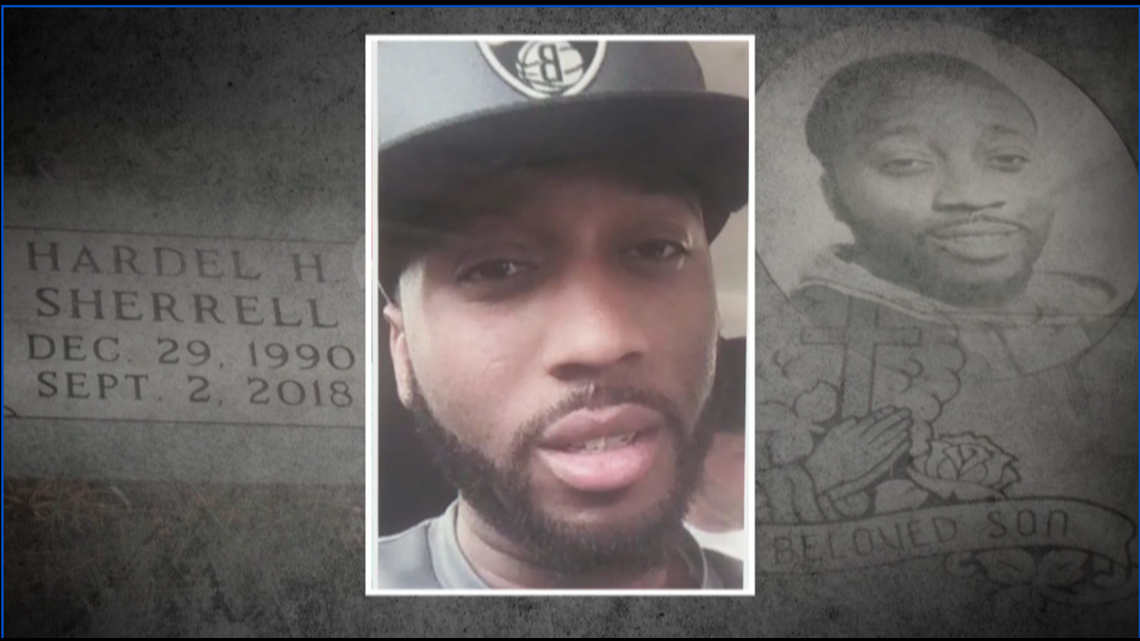

Hardel Sherrell suffered for days and pleaded for help before dying all while his jailers and many of his care providers believed he was faking, as KARE 11 has extensively reported.

News of the grand jury investigation comes one day after the state medical board suspended the doctor responsible for Sherrell’s care, Todd Leonard, calling his actions “egregious.”

In addition to recommending discipline for Leonard, the Administrative Law Judge who heard the case called for an investigation of “all who callously disregarded their duty to this man.”

The grand jury may be investigating Sherrell’s other caregivers and jail staff. The jury subpoenaed Sherrell’s mother, Del Shea Perry, asking her or her lawyer to provide any records they have regarding her son’s death and did not specifically name Leonard.

“This is a mother who will fight to the very end until there are people who are held accountable for what they have done,” Perry said Wednesday.

Del Shea Perry has waited for years for action to be taken following her son’s death. She called Leonard’s suspension “a small victory. But we’ve got a long way to go.”

Leonard is the founder and President of MEnD Correctional Care, which provides health care to dozens of jails and thousands of inmates across five states, including Beltrami in 2018.

The medical board adopted a report written by administrative law judge Ann O’Reilly who reviewed the case and found that Leonard, as the medical director of the Beltrami County jail, “demonstrated a careless disregard for the health, welfare, and safety of his patient.”

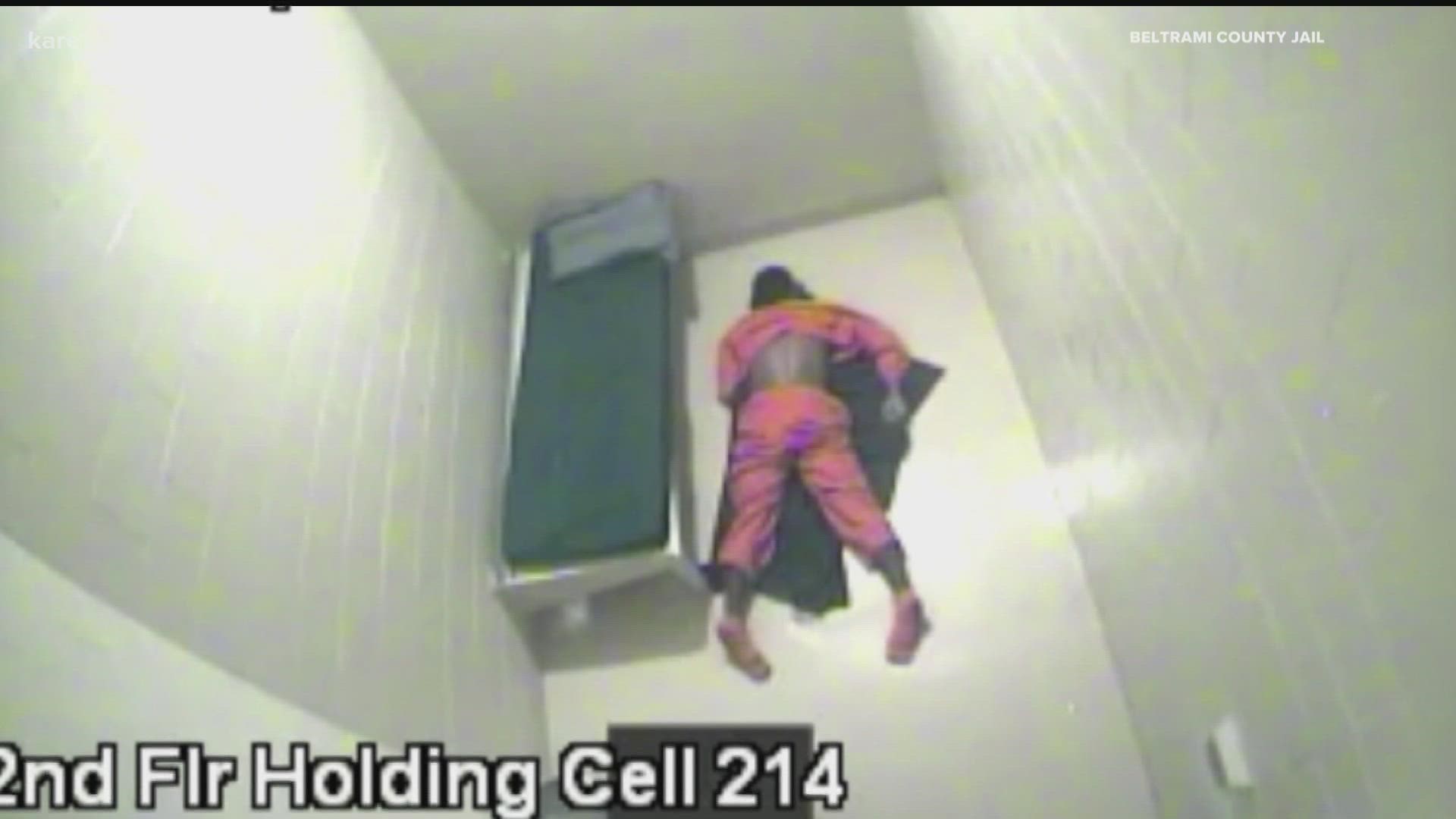

O’Reilly’s report carefully laid out the neglect from many of his caregivers that led to Sherrell’s death. As he became paralyzed from the waist down, Sherrell lost control of his bowels. He begged for help and laid on his cell room floor unable to move in his own waste. Yet many jailers and care providers refused to help him.

“Even in his final hours,” O’Reilly wrote, “as he laid unconscious, half-naked on the floor of his jail cell, white foam coming from his mouth, they still did not believe him.”

Several days before Sherrell died, one of MEnD’s nurses examined him and tried to get the inmate to a hospital. Yet a jail administrator overruled the decision, saying he was a flight risk. Instead of calling the administrator and advocating for his patient, Leonard “yielded to the administrator’s will and discretion,” O’Reilly wrote.

Later, when another MEnD nurse suspected Sherrell had been faking, she watched a video to determine if he was telling the truth. However, the video she watched had been recorded of him earlier when he was in better condition, which appeared to contradict his statements.

When the nurse described what she observed to Leonard, he ordered the nurse to discontinue a medication and take away his wheelchair.

Sherrell would eventually be sent to the hospital only after Nurse Practitioner Stephanie Lundblad examined him and determined that he needed immediate care.

But based partly on false and incomplete information provided by the jail and MEnD staff, hospital doctors also suspected Sherrell had been faking and sent him back to the jail.

Still, as part of Sherrell’s discharge instructions, doctors wanted him to be returned immediately should his condition worsen. Yet Leonard never sent Sherrell back when his condition got worse, in part because he never asked for his patient’s vital signs, O’Reilly found.

‘Love contract’

At times O’Reilly’s report went beyond Sherrell’s care and described problematic practices at MEnD.

The company’s nursing director, Michelle Skroch, first started at the company several years ago after she was hired straight out of college. Eventually she and Leonard began a romantic relationship and she moved in with him. MEnD’s attorney drew up a “love contract,” for the two of them, O’Reilly wrote, “to openly declare their romantic and professional relationship.”

Skroch developed training materials for MEnD employees and correctional staff that made light of the inmate population, O’Reilly wrote. One of the training materials included a cartoon of a doctor looking out of a window as a prisoner laid on an inmate table, with the doctor saying, “you should get out more.”

A slide about patient care included a cartoon of a woman in a bathroom saying, “Showering won’t be enough today. I’ll need to be autoclaved (sterilized).”

Skroch would be a key figure in Sherrell’s care. She was Beltrami’s nurse on duty in the two days before his death. According to O’Reilly’s report, after a correctional officer told her about Sherrell’s condition, she waited two-and-a-half hours before seeing him.

Even then, she stood about 10 feet away from Sherrell as he laid paralyzed in his own filth and spoke with him for only three minutes, failing to check his vital signs.

“In essence, (Skroch) stood as far as possible from (Sherrell) and provided him no care whatsoever,” O’Reilly wrote.

In a statement Tuesday night, Leonard called Sherrell’s death “a tragedy,” but said, “to my core I believe our care was appropriate, especially given the incredibly rare nature of this patient’s condition.”

According to O’Reilly’s report, Leonard never took action against any of his employees involved in Sherrell’s care. Leonard said in an interview with an investigator that he was ‘“very proud of the way (Skroch) handled the case’ by ‘caring for this patient’ and ‘providing dignity for him,’” O’Reilly wrote.

O’Reilly implored counties to scrutinize their relationships with MEnD, saying what happened to Sherrell “must never happen again.”

That’s been happening even before her report. Beltrami County voted last year to end their contract with MEnD. Dakota County followed at the end of December.

The Minnesota Department of Corrections, which has oversight of the jails, will ensure that counties which contract with MEnD will provide appropriate care to inmates, a spokesman said Wednesday.

“As for the action taken, we are glad the Board acted as they deemed necessary to protect more people from harm,” the spokesman added. “People being held in custody deserve appropriate medical care. We are exploring rulemaking that would help ensure medical needs of those held in jails are addressed in a systemic and timely manner and that would prevent jail personnel from overriding the direction medical professionals.”